Reconsidering Intercountry Adoption: Who Wants to Adopt and Who Could Be Adopted?

Adoption Advocate No. 57

This article, which is based on a working paper presented at the Ninth Annual Adoption Law and Policy Conference in March 2012, utilizes the 2006-2008 National Survey on Family Growth (conducted by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control), the USAID/UNICEF Demographic and Health Surveys, and UN and U.S. Census Bureau data in order to profile adoptive parents in the United States and examine the serious and often life-threatening dangers faced by orphaned and vulnerable children.

Much has been written about the recent and steady decline in intercountry adoption, and its consequences for the many millions of children worldwide living outside parental care who lack safe, permanent families of their own. Despite the numerous challenges and threats to which orphaned children are exposed some individuals and organizations nonetheless support ending or severely limiting the already low numbers of intercountry adoption, due to concerns regarding its policies and practices.

Among the strongest ethical objections voiced by those opposed to or skeptical of intercountry adoption are the stark differences between birthparents and adoptive parents – differences often defined in terms of privilege and financial resources as well as social background and cultural identity. While these concerns are undoubtedly important, they cannot make the case for severely restricting or eliminating intercountry adoption programs, given the great and undeniable danger posed to children that remain in institutionalized care.

It is important to study outcomes for children who are not adopted due to policies that slow or shut down intercountry adoption programs. When international adoption numbers drop, what are the consequences for those children who might have been adopted? It is the potential impact on children that should and must carry the greatest weight in the ongoing debate over intercountry adoption.

Who wants to adopt?

According to one recent estimate, there are over 900,000 Americans seeking to adopt at any given time1. Each year, American families adopt approximately 50,000 children out of foster care, 18,000 via domestic infant adoption, and 10,000 children via intercountry adoption. Together, these totals represent 93% fewer completed adoptions than individuals actively seeking to adopt.

According to the 2006-2008 National Survey of Family Growth, the reason potential adopters stop trying to adopt is their inability to find an available child to adopt.2

Who could be adopted?

In August 2008, UNICEF estimated that there were 132 million orphans worldwide, 13 million of whom were dual-parent orphans – children that had been orphaned by both parents. In this report, UNICEF asserted that “the vast majority of orphans are living with a surviving parent.”3 By January 2011, UNICEF’s global orphan estimate had swelled to more than 150 million, with 18 million orphaned by both parents.4

The ratio of dual-parent orphans in sub-Saharan Africa alone to the total annual number of intercountry adoptions by American citizens (approximately 10,000) is 910:1. International adoptions into the United States are miniscule compared to the number of children in sub-Saharan Africa who have lost both parents. Current rates of intercountry adoption are barely making a dent.

While UNICEF is technically accurate in noting that a majority of orphans live with a surviving parent or other relative, the enormous number of children that have no surviving parents and no other family members able to care for them should underscore the potential of adoption to positively and permanently impact the lives of millions of children.

When considering the plight of 153 million children, even a small percentage of children that could be adopted results in large absolute numbers. If only 1% of orphans worldwide were able to be adopted, this would result in 1.53 million adoptions every year; even just one-tenth of 1% of orphans would result in 153,000 international adoptions annually.

Orphaned children in middle- and low-income countries are at significantly higher risk of suffering a wide range of negative physical, mental, and behavioral outcomes as compared to their non-orphaned peers.5 Orphans in middle-income countries typically experience adequate physical development but poor mental health outcomes due to their institutionalization. Orphans in poor and lesser-developed countries experience better mental health outcomes relative to middle-income orphans, but poor physical health outcomes. While orphaned and vulnerable children are, on average, 5-10% less likely to attend school than their non-orphaned peers, their material deprivation is significantly higher – by 20-30%, on average.

Most tragically, a great number of orphaned and vulnerable children do not survive to adulthood. In 2010, the number of orphaned children under age five who died in sub-Saharan Africa was more than 30 times the number of all intercountry adoptions by American parents.

Putting the numbers in perspective

The idea that even large increases in international child adoption into the United States will somehow overwhelm other countries, or materially reduce the number of children available for domestic adoption in their home countries, is simply not supported by the facts. The difference between the vast number of orphaned and at-risk children and the incredibly low number of intercountry adoptions by American parents is too large to have an adverse effect on domestic adoption programs in other countries.

If the current number of intercountry adoptions into the United States were to increase tenfold, this would still represent only one-half of 1% of dual-parent orphans worldwide, and less than one-tenth of 1% of all orphans.

If the percentage of dual-parent orphans worldwide adopted by families in the United States were to rise to just 1% of the global total number of orphans, this would still increase annual intercountry adoptions into the U.S. by approximately eighteen fold.

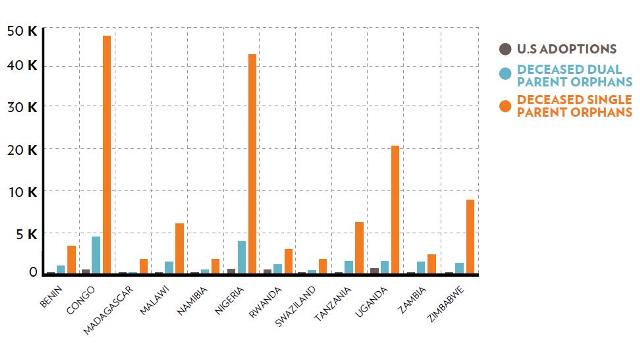

Even if we focus on the most vulnerable, the disparity between the number of orphans in need and the number of adoptions is enormous. Figure 1 shows the number of single- and dual-parent orphan deaths compared to the number of adoptions into the United States from sub-Saharan Africa. There are more dual-parent orphan deaths in sub-Saharan Africa than adoptions into the United States.

If our goal is to protect and promote the best interests of orphaned children, it is difficult to understand how witnessing 300,000 orphan deaths annually while simultaneously limiting international adoption can be defended as sound policy. There are large numbers of qualified families seeking to adopt that could help reduce the enormous number of deaths amidst this most vulnerable population of children. Without discounting the many issues in intercountry adoption, or underestimating all the work that must be done to address the complex factors that lead to such large numbers of orphaned and abandoned children worldwide, it must be acknowledged that remaining alive, in good health, with loving parents, is in the best interests of children who find nurturing families through adoption.

Comment: National Council For Adoption

Despite the growing orphan crisis and the life-threatening dangers faced by orphaned and vulnerable children, the rate of intercountry adoption continues to decrease each year and has been plagued by slowdowns, moratoriums, and program closures such as the recent Russian ban on adoptions to the U.S. It is likely that intercountry adoption numbers will continue to decline in the future.6

It is the position of the National Council For Adoption that intercountry adoption is not necessarily the first or ideal option for all orphaned or abandoned children; rather, intercountry adoption should be part of a holistic, comprehensive, child-centered continuum of care that considers time-sensitive options for children, including keeping children with their biological parents or kin whenever possible, and in their countries and cultures of origin if domestic adoption is an available and viable option. More must be done to prevent family dissolution, give parents the resources and help they need to continue to parent their children, seek out and support existing kinship connections if parents are absent or deceased, and develop and strengthen domestic adoption programs for in-country placements – whenever such options are possible and can occur within a realistic time frame that takes into account the child’s need for timely permanency.

However, for many children, intercountry adoption may indeed represent their best chance at achieving safety and stability in nurturing, permanent family-based care. Child welfare advocates should recognize the fact that keeping more children in institutionalized care puts physical health and safety as well as stability and permanency out of reach for countless children – and, in too many cases, leaves them vulnerable to poverty, disease, and even death. Many institutions are unable to provide the kind of care that is necessary for a child to thrive, especially during the early years when nurturing is so important.

Research has consistently shown positive outcomes for the vast majority of children adopted internationally, in sharp contrast to the poor outcomes shown in numerous studies of orphaned and vulnerable children living in institutions. While it is essential to protect and promote the good and transparent adoption practices that all children, birthparents, and adoptive parents deserve, the dire consequences for children when intercountry adoption programs are restricted or closed should remain at the forefront of this ongoing discussion, and must be taken into consideration when making important and impactful decisions about child welfare policy.

References

- Jones, Jo, “Adoption Experiences of Women and Men and Demand for Children to Adopt by Women 18-44 Years of Age in the United States, 2002,” Series 23, No. 7, August 2008. Data from the National Survey of Family Growth.

- Ibid.

- UNICEF Media Centre Position on Orphans accessed on June 24, 2012 at http://www.unicef.org/media/media_45290.html

- UNICEF Orphan data accessed on June 24, 2012 at http://data.unicef.org/

- For more, see: Gamer, Gary, “Earlier is Better for Family Care: What Research Tells Us About Young Children and Institutionalization,” Adoption Advocate No. 50 (National Council For Adoption, August 2012). Available online at: https://adoptioncouncil.org//publications/2012/08/adoption-advocate-no-50

- For more on intercountry adoption numbers worldwide, see: Selman, Peter, “Global Trends in Intercountry Adoption: 2001-2010,” Adoption Advocate No. 44 (National Council For Adoption, February 2012). Available online at: https://adoptioncouncil.org//publications/2012/02/adoption-advocate-no-44